Having the freedom to choose what our final project was in this class gave us not only a unique set of options but also a responsibility to choose something interesting, powerful and connectable to the class as a whole. Not every class offers the opportunity to choose the final exam topic. However, Digital Humanities, in my opinion a frequent “trier of new things”, seemed like the perfect class to do just that.

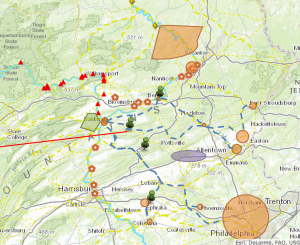

Our research question was, “After the Powell Diaries and into the beginning of the French and Indian War, is Shamokin still a significant place? Are as many people traveling through it? What impact has the outbreak of the French and Indian War had on Shamokin geographically?” We wanted to understand how time has had an effect on Shamokin. It was clear through the Powell Diaries that it was a place of significance in central Pennsylvania and beyond. However, we were curious as to whether it would withstand not only time but the increasing danger that was headed its direction in the 1750’s. To accomplish this, we decided to create an arcGIS map of the areas within the diary and then a story map journal to tell the story visually of what occurred in the diary, and thus answer our question.

Initially, we were given the possibility by Professor Faull of reading the last twenty pages of the Diary of Shamokin 1755, which detailed the last three months of the town and what was going on in and around it. We were given a digital copy of the diary, and divided it up evenly between the two of us: Matt took the first ten pages and I took the second ten pages. We then proceeded to read it and highlight places to put into the map.

As we did this, we put the locations into an online excel spreadsheet that allowed us to view and describe the locations, and also to manage duplicates. In addition, as you can see in the image of the digital text, some of it is underlined. Later on in the process, we realized that it was important to implement quotes or events from the text. When we realized this, we went back and re-read the material, underlining or bolding certain parts of text that helped improve the map.

Once this process was complete, we were ready to start the map. Having already familiarized ourselves with arcGIS, getting started was not difficult. Matt and I created separate maps according to our ten pages, the plan being that at the end we would put the layers of my map into his to make the finalized version.

Starting with one of Professor Faull’s basemaps, we each put places into our individual map. The second half of the diary did not focus too much on places or locations, but rather the change that started occurring in Shamokin and the presence of violence due to escalation amongst French and British forces and the Indians. I realized quickly that in order to effectively tell the story, I needed to use specific parts (events, people) of the diary.

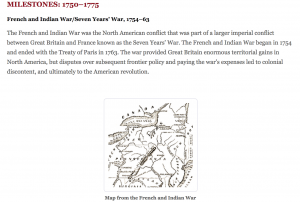

In addition, I realized that background information on the French and Indian War was key. I found reputable sources online and read about the causes of the war and the effect it had on communities, colonists and natives. This gave me a deeper understanding of what exactly was going on in the fall of 1755, what led up to that point, and how the future of the landscape would look as the war went on.

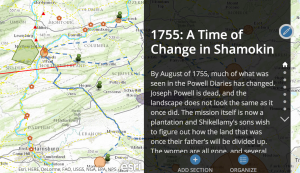

As the map developed, it became a full, well thought out visual depiction of the diary. We wanted to have points and areas on the map that thoroughly showed what happened in the diary with as much depth as possible. In addition, color coding and path drawing were equally as important. Once we imported my layers into Matt’s map, we had a complete version of a visual representation of this Diary of Shamokin.

The completion of the map brought us to the point where we were able to now begin the story map journal. With the map journal we wanted to fill in any areas we missed along the way. In addition, we wanted to basically summarize the journal from day one to the end. This would give the audience a feel that they really did experience the events and places of the diary for themselves.

We experienced difficulty throughout the project. It was often difficult to meet in person due to conflicts, so much of the project was done individually while communicating with one another. This is not as easy as it sounds, and sometimes we ran into spots in the project where it would have saved time to meet in person, but it just was not possible. In addition, we chose to use one account to combine layers and make the story map, since it is impossible to work on the same project with two accounts. It was often difficult for me to switch accounts back and forth.

When reexamining my analysis of a professional scholarly digital humanities research project, I understood that at the end of the day we are answering a question or set of questions in a unique, thought-provoking way. I also saw a professional humanities research project as a organized, step-by-step method for answering a particular question. There are so many ways to do this, however, and Jiayu and Qijing made a really good point in their explanation of their project when they explained how they flipped the process of coming up with their research question. Instead of coming up with the question, then researching, they researched first so as to ask the right question. This caught my attention because it shed even more light on how a professional scholarly digital humanities research project can go an unconventional direction and still complete the same task, possibly even more effectively than normal. With digital humanities, one is not always confined to the tight space of typical research based problem solving, and because of this there is endless room for improvement