Over the last two weeks, we did close reading on Powell Diary, built our GIS Data Dictionary, created our own story maps and finally published the maps through a web mapping application. In my story maps, I focused primarily on the connections between Shamokin and Native Americans. Through maps and spatial thinking, I tried to find the answers to the following two questions. Where did the Native Americans visiting Shamokin came from? And where did the Native Americans living in Shamokin visit?

In his article “The Potential of Spatial Humanities”, David J. Bodenhamer states that space “has assumed a more interesting and active role in how we understand history and culture”; “GIS is a seductive technology, a magic box capable of wondrous feats, and the images it constructs so effortlessly appeal to us in ways more subtle and more powerful than words can.” I couldn’t agree more. When reading the text “January 28. came two Indians from the War with the cattobats… They two that are escap.d left the other and came behind a Towne of the Cattobats expecting to kill some as thay Came out… Out of the Town about 30 men very Swift… cut thier flesh all over thare boddyes to the bone while thay ware yet alive”, people may place their attention on the barbarity of the Cattabaw. However, having read the map, people would be surprised to find that the distance between “a town of the Cattabaw” and Shamokin was actually very great. It can be further interpreted that the two Indians were very persevering that they trekked a long way with serious injury, and Shamokin was an important town that gave the two Indians a sense of security.

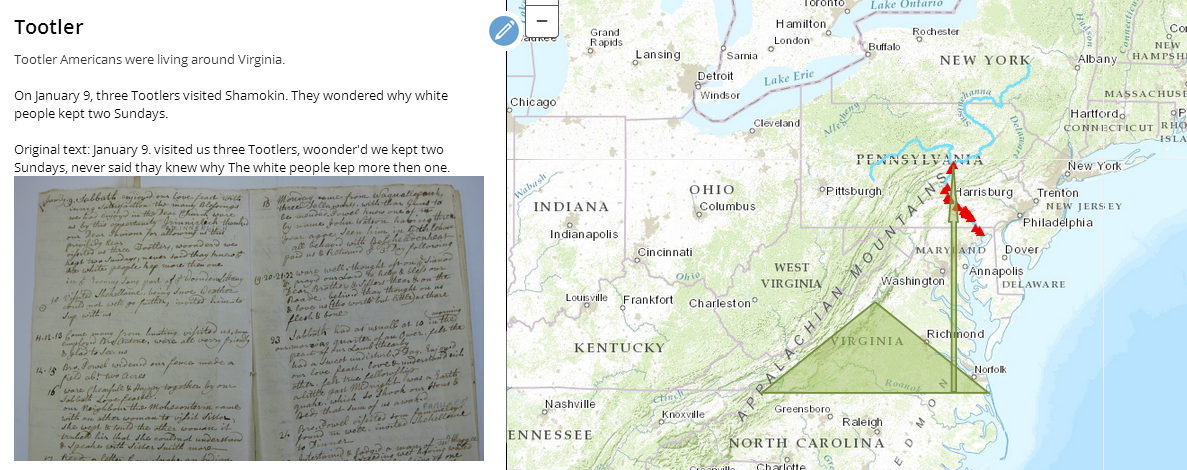

Though mapping is a very important component of GIS, it’s not the only thing that makes GIS meaningful. Time, texts, explanations and images all play important roles. As Bodenhamer has noted, “GIS was part of what might otherwise be called digital history rather than spatial history because the approach was fundamentally archival and textual.” The web mapping application is a good example. In the application, readers are provided the map, the explanation of the map, the original text and the image of the archive. In his article, Bodenhamer points out a challenge: instead of musing about how to get humanists to adopt GIS, we should think about how to make GIS a helpmeet for humanists; how GIS can represent the world as culture, rather than simply as mapped locations. I believe that web mapping application is the answer to this challenge. It presents the story, not just the map.